“FLOATING OUTSIDER”

Narrative written by Ann de Forest

Photos by Dave Tavani

She refers to herself as “Floating Outsider.” Stateless, she requests she be nameless here. One day she will shout out her story, she says. One day she will seize the opportunity of a platform offered her to tell the truth about the Bidoon in her native Kuwait.

Right now, though, her father, brother, and sister – also stateless – remain in Kuwait, and she worries that making a public statement here could endanger them there. “His [her father’s] file is still being studied in Kuwait,” she says. “I don’t know why.”

F.O.’s father is Bidoon – a word that throughout the Arab world means “without.” As in “without nationality.” In Kuwait that outsider status extends even further: Without citizenship. Without basic rights – to education, employment, or medical care.

A student of Comparative Literature, F.O. loves to tear words apart to expose their true meaning. “I wound words,” she says. Embedded in the word Bidoon is another Arabic word, dūn. It means “low, inferior.”

Her father is Bidoon because his family are Bedouin, descendants of the nomadic desert peoples that, F.O. says, were the first Arabs. Kuwait, by contrast, is a country less than 100 years old. In the modern Middle East, where borders have been drawn, nation states established fairly recently, these ancient nomadic people no longer have a nationality.

Because of their father, F.O. and her siblings are Bidoon as well. Their mother, though, is Kuwaiti, with the full rights of citizenship. This makes their children’s status even murkier. Because of their mother, F.O. and her siblings could attend public school and go to the doctor and dentist, “privileges” other non-Kuwaiti are excluded from. But full citizenship in Kuwait can be passed only through the father. If her parents’ divorced, the children would be given full citizenship. Some well- meaning friends have advised them to do so. “My father refuses,” she says. “Because it is absurd.”

Her identification documents are masterpieces of bureaucratic doublespeak. The back of her state-issued I.D. contains a disclaimer: “This I.D. is not to be used as identification.” Still, Kuwait requires her to carry one. Her passport, dove grey as opposed to the standard Kuwaiti blue, is just as tangled in contradictions. “Nationality: None/Kuwait” reads a line by her photograph. She flips the pages to show the restrictions imposed upon her. The only country she is permitted to enter is the United States. “I could write a dissertation about my passport,” she says. That grey cover might as well be a red flag signaling her outsider status. Because of its color, she says, she is pulled from the airport line and into a closed room for questioning every time she travels.

F.O. knew nothing of her statelessness until she was in fourth or fifth grade. On a school trip, a friend happened to notice a document listing all the kids in their class. Every child had a K by their name, except for F.O. Next to her name were two initials, NK. Her friend turned to her. “You don’t look like an alien,” she said.

That moment remains frozen in her mind. “I can remember what I was wearing,” she says.

F.O. went home and asked her aunt to explain what those initials could mean. “Non-Kuwaiti,” her aunt answered. “You’re not Kuwaiti.”

The shock of that first discovery led her to investigate further on her own. She dragged suitcases out from under her father’s bed, six or seven suitcases that held briefcases inside them, briefcases filled with documents – birth certificates, school transcripts, her parents’ marriage license. She was surprised to see her father’s birth certificate, issued when he was an adult, showed an estimate of his age. When she questioned him, he told her how the government had examined him and then determined, based on appearance alone, what year he was born.

She understood the message implicit in her father’s hoarded documents. “In order to become something in this life, you need to have a piece of paper. Maybe that is why I’m studying all the time and trying to get all these degrees – as proof that I exist.”

She recounts other humiliations and injustices inflicted on ordinary people, who are simply trying to live their lives. She tells a story about her brother’s friend, “stateless on both sides”, who wanted to marry his girlfriend. In order for Bidoon to marry, F.O. explains, they must “forcefully” acknowledge that they are citizens of another country, in other words lie about their status as ‘stateless’ on a signed document. If the stateless person refuses, the Ministry of Justice in Kuwait won’t certify the matrimonial contract. “This brutal act ,” she says, “leads many stateless people to say they raped this woman so that their matrimonial contract gets certified at the Central Agency for Illegal Residents in Kuwait. “ That was the solution a lawyer offered her brother’s friend: if he went to the police and claimed he raped his girlfriend, and she backed up his claim, the law would then force them to marry.

Her family has been forced to endure absurdities as well. Her father used to work as a ghostwriter for government officials, crafting their speeches and public statements that will persuade people to vote for them. “He knows more about the way the government works than they do,” says F.O. Her sister, an excellent student, had to fight for a place at the public university. Bidoon children to Kuwaiti mothers can attend state university only if the spots aren’t filled by Kuwaitis, regardless of grades and test scores. Now working as a physical therapist, she earns one-quarter of what Kuwaitis earn in the same job. Despite these and other countless indignities, her father has tried to convince F.O. to stay in Kuwait. He even arranged for a family friend, a professor, to encourage her. That friend suggested one path to citizenship: find a nice Kuwaiti to marry. “There are ways to live happily in Kuwait,” she said, “but that’s not me.”

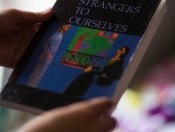

She resisted limitations from a young age. As she got older, she grew increasingly “annoyed”, she says, at her parents for never acting or reacting, but always waiting, waiting. She didn’t want to wait, like they did, for society to change, for their lives to get better, for their rights to be handed to them. After she earned a B.A. in English in Kuwait, she applied for an M.A. in Comparative Literature at a university abroad without her parents’ knowledge. Her father opposed her leaving, and then, when it was clear she would leave, wanted her to travel with a guardian. Her mother, though, encouraged her independence and offered to pay for her education. In the foreign university, she found freedom and, for the first time, a sense of belonging. Liberated in that country’s more open and stimulating society, she found her truer, more enduring home in literature. Poets and philosophers speak her language and explore ideas – like loss, or strangerness (the subject of her thesis) – that resonate personally and politically. She developed a habit, which she still keeps today, of opening books at random, “like a horoscope,” and letting whatever words appear speak to her. “I try to find answers in books, and I find them in poetry,” she says.

Her newfound freedom emboldened her. When the Kuwaiti embassy in the foreign country invited her and other Kuwaiti students to a dinner celebrating the nation’s Independence Day, she seized the opportunity to speak up. She found herself seated next to a well-known woman, a former diplomat and representative for the Kuwaiti department of foreign affairs. F.O. spoke her new country’s dialect. The woman, assessing her, said, “Your mother I assume is non-Kuwaiti?”

F.O. looked her in the eye, her voice suddenly sharp. “No,” she said. “I am stateless. Imagine that. A stateless person is sitting next to you.”

The woman responded in Arabic, “You don’t really have roots in this country. You are just like a deserted plant in the desert. Your father came out of nowhere.”

To call someone without roots is a deep insult in Arabic, F.O. explains. “I know they think of us as less than human beings,” she says now. “This was very humiliating.”

F.O. and her brother, who had accompanied her to the dinner, both started yelling. “Can you tell this woman to shut up?” asked her brother. “Because she is really insulting us.” The woman screamed back. “Why are you talking in non-Kuwaiti?”

F.O. answered, “Because here I am free. I am talking because this country is a metaphor for the most free country, the place to prosper. I am Bidoon and I’m free.”

A few days later, F.O. was called to the cultural office of the Kuwait Embassy and asked to apologize. She told the woman, a Palestinian whom she respected, “No. There is no funding that you can cut. There is nothing that woman can do to me.”

After her M.A., she returned briefly to Kuwait, where she taught English at her college for one year. She engaged her class of adult learners in conversations about prejudice against non-Kuwaitis bias, and believed she changed their thinking. She lasted one year. The pay was okay, but this feeling of not belonging to this place was in my mind all the time.” She applied to American graduate schools, for a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature, again without her parents’ knowledge. She was accepted and offered her a scholarship, and F.O. left the country that doesn’t acknowledge her existence. She is sure now she will never go back to live in Kuwait. “If God comes to earth and tells me to come back to Kuwait, I’m not going to,” she says.

When her advisor moved to a different university abroad, F.O. did not follow, in part because her passport prevents her from traveling there. She instead transferred to a university in Philadelphia, where she has found a community unlike any other she has ever known.

“I’m happy in the city. I love living in this place. …I feel like a human being here. When I say I’m stateless, people say, ‘okay, that’s cool.’ There’s no discrimination against me. I feel this place has given me the chance to become the person who I really want to be.”

The poets she reads, the topics she studies, address the same themes that have troubled and attracted her from that day she saw the “NK” next to her name. She is interested in the distinctions between outside and inside, between presence and absence throughout the Arab world. Her encounters with poets from other Arab countries have led her to reflect on her family’s rootlessness in a new light.

Her father’s people, her people, are like rhizomes, she says. Shallow rooted, they spread across the land in a wide net or chain. Rhizomes are easy to dig up and break apart, but nearly impossible to destroy. While the former diplomat in Beirut insulted her family by comparing them to a desert plant, F.O. now finds strength in that metaphor. Rhizomes move. Rhizomes are free.

Unlike many displaced from the land of their birth, F.O. rejects the concept of nostalgia. “I always make fun of people who say they are missing home, which might be very annoying to some. In Arabic the essence and core of things is lack. But when you lack something you might just spend your life missing it. You feel empty.”

All she lacks, “is this feeling other people have about missing home. I would rather be a universal citizen of the world. If I belong to anything I belong to the world of poetry. It keeps me sane in this unnecessarily tense world.”

Emi and Afaq Mahmoud

Emi and Afaq Mahmoud  Rajie Cook

Rajie Cook  Cocoa Mahoney

Cocoa Mahoney  Yasser Allaham

Yasser Allaham  Gulnora Ravshan

Gulnora Ravshan  “Ahmad” & “Zainab”

“Ahmad” & “Zainab”  Jack and Gloris Dunnous

Jack and Gloris Dunnous  Maria Turcios

Maria Turcios  Lafayette El

Lafayette El  Tara O’Brien

Tara O’Brien  Sophia Simpson

Sophia Simpson